Swasey Chapel, filled to the brim with students, faculty, and the Board of Trustees, rang clear with the melody of President Knobel’s voice on Friday. Quoting from Billy Joel’s “Piano Man,” he musically wondered, “Son, can you play me a memory?; I’m not really sure how it goes/But it’s sad and it’s sweet and I knew it complete/When I wore a younger man’s clothes.” The air at this Academic Awards Convocation, thick with the pomp of regalia, felt itself loosened by Knobel’s humility and retrospection. He talked about the meaning of “clothing,” appropriate for a crowd filled with caps and gowns, and underscored its philosophical and existential weight.

“Those we recognize and celebrate today remind us that the acquisition of an education or the development of character is not accidental or passive,” Knobel said, referring to the many professors and students who would be recognized for their achievements. “Far from it. We clothe with considerable intentionality.”

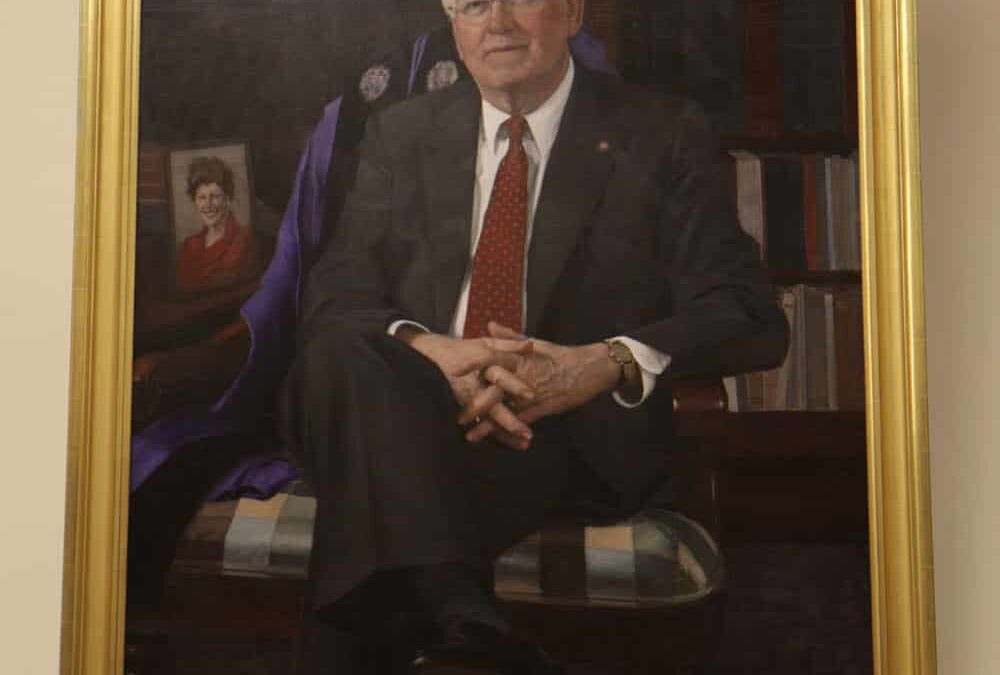

Intentionality – perhaps no other word can better describe the character of Denison’s outgoing chief executive. Students and staff will remember him as composed, jovial, conversational, cherubic, a little distant – perhaps the very model of the university president.

The nineteenth president of the University, Knobel assumed his position in the summer of 1998, after Denison’s previous president, Michele Tolela Myers, went on to serve as President of Sarah Lawrence College in Yonkers, N.Y. He has governed Denison for 15 years, and will depart as its second-longest serving president, surpassed only by A. Blair Knapp, who served for 17.

On the eve of his final two months in the office, The Denisonian sat down with Knobel to tell the full story of this paramount figure.

“A toddler in Mayfield Heights”

Dale Thomas Knobel was born in 1949 in East Cleveland, Ohio, and “grew up in a variety of Cleveland suburbs” as his “family moved out from the center” of Cleveland proper. The Knobels lived in Mayfield Heights and Lyndhurst in Cuyahoga County before moving to Worthington in the Columbus area. There, Knobel was enrolled in Worthington High School and “didn’t move back to the Cleveland area…until the middle of high school,” when his family settled in Hudson, Ohio in Summit County, about 30 miles south of downtown Cleveland.

“Neither of my parents had the experience of attending a college like [Denison],” said Knobel. His father, who “came from a working-class family in Cleveland,” attended Fenn College, a YMCA community college in downtown Cleveland, “founded in the 1800s for immigrants and the children of immigrants.” Fenn College would later be absorbed into Cleveland State University. Knobel’s mother “never finished college,” although she did attend Kent State University and Case Western Reserve University – then called Western Reserve College. Both of them “got caught up” in World War II, and Knobel’s father joined the army. Upon his return, he was able to go to the Ohio State University on a G.I. bill, where he earned an M.B.A. when the degree was “still rare.” With this degree, the elder Knobel was able to pursue a career with Standard Oil of Ohio, and rose to a senior executive position and “oversaw the retail business of the company.”

Knobel is one of three siblings. He has a brother in North Canton, Ohio, whose two grown children live in New Albany and Columbus; and a sister who “is a United Methodist minister” in Olney, Md., a suburb of Washington, D.C., who herself has three children.

At Hudson High School, Knobel met his future wife, Tina H. Jamieson, who shared many of his childhood experiences. Her father, too, worked in a career where he was transferred around the country frequently. The to-be Mrs. Knobel was born in the “same Cleveland hospital” as Dale, and lived in Kalamazoo, Mich., and Cedar Rapids, Iowa before coming to Hudson “in the middle of high school. So here was a new boy and a new girl,” said Knobel, “in what was then a small high school… and so it was destiny, I guess.” They started dating in their senior year and would maintain their relationship through college.

“A remote college town”

Speaking of his own college search, Knobel highlighted his father’s influence. Fenn College, the elder Knobel’s alma mater, “did not seem like a real college to him. He saw pictures,” said Knobel, “of Denison, or Yale, or Northwestern, and these looked like real colleges to him.” These prestigious universities, said Knobel, seemed “like Valhallas” to his parents. “We would drive here to Granville and say – now that’s a college! – and the same would be true of Kenyon or the College of Wooster. And so when I looked at colleges, I was interested in a liberal arts college, and I confined my search primarily to Ohio liberal arts colleges.

“I was looking for a college that probably…would feel comfortable given the community that I was from and the students who I knew,” said Knobel. “I was a soccer player, and Denison had a great soccer program, and Hudson had a great soccer program.” He cited the opportunity to play on Big Red’s team as a draw, as well as the proximity of Heidelberg College, where the future Mrs. Knobel was planning on going.

“So I came here to Denison and it in fact it was sort of exactly what I thought,” said Knobel. He was inducted in the fall of 1967. “At the time, Denison was a much more homogeneous place. There are good things about homogeneity,” he continued, “but there also some things – from an educational standpoint – that maybe aren’t so good.”

Describing the demographics of Denison at the time, Knobel said, “The students were mostly all white, all suburban, all upper-middle class. These were young people I felt very comfortable with, because they were the same people I’d gone to high school with.”

“I enjoyed my year on the soccer team. I particularly enjoyed my classes, and I thought that I had some of the best teachers I’d ever had.” Knobel specifically mentioned professors emeriti Dom Consolo in the English department and Ron Santoni in philosophy.

Looking back, Knobel emphasized that he feels Denison has kept its positive attributes while improving on weaker areas immensely. “You couldn’t know everyone, but you could know a wide range of fellow students.” Denison was, at the time, a small school attempting to grow. Knobel’s class of ‘71 was the first to hit 600 students – beforehand, the student population had plateaued at a size of about 1600. “It was ramping up by about 100 students a year,” he said.

A large part of this expansion program was an “aggressive” campaign to improve living spaces. In his freshman year, Knobel lived in “New Men’s Dorm,” which is today Shorney Hall. “West Quad was for men and East Quad was for women” at the time. Shepardson Hall was also constructed in Knobel’s first year. Knobel semi-fondly recounted “trooping across” campus from West Quad to Huffman dining hall, which was then the only food option on the Hill; Curtis dining hall opened after his only Denison spring break, to “great excitement.”

Knobel noted that the “intimacy” of campus has remained unchanged, although the academic culture was vastly different during his studies here. For one, enormous lecture classes were still common. Slayter Auditorium, for example, was still regularly used for introductory level classes. “300 kids with lectures down on the stage” for a history of Western civilization course or “a psychology lecture [that took place] in the old life science building – what we now call Higley” were commonplace affair, said Knobel. “We don’t teach like that anymore.”

“The complexity of the student body” is another thing that was different in the late 60s. “There were a handful of African-American students; there were one or two Hispanic students; there were three or four international students; there was modest financial aid available, so there was a great deal of socioeconomic homogeneity,” he said. “People tended to come predominantly from suburban backgrounds, very few from either inner-city or urban backgrounds, or small-town backgrounds.”

“Part of it also is where we are,” he continued. “In 1967 this was considered a remote college town, remote from Columbus. It was hard to get to Columbus – it was way out there, more in the way…Gambier still is today,” referring to Kenyon College. “There were cornfields between here and Newark, even. This was considered a kind of isolated college town…There were no shopping malls, no discount stores,” not even in Newark.

But it was primarily the issue of diversity that caused Knobel to reconsider his education on the Hill. “I began to think very quickly,” he said, “oh my, maybe it’s not homogeneity that you want, maybe it’s heterogeneity that you want – to be exposed to fellow students who have not shared your experience.” Speaking of his decision to transfer from Denison, he said, “Probably before my first semester was over, I thought… that I needed to get out.”

“In the back of my head was Denison”

“I transferred to Yale because I had known an African-American student – several years older than me – who had gone [there], and that sort of put into my head that it was a place that was already seeking diversity,” said Knobel, “in a way that we weren’t quite ready to yet.”

“Yale itself, just a few years earlier, had been a very homogeneous place too,” he said, “but in about 1964 or so, a forward-thinking admissions dean had come to Yale and had really begun to change the character of the student body.” Knobel was accepted as a transfer student and moved to New Haven to begin his sophomore year, in the fall of 1968. “I had exactly the experience I was looking for,” he said. “I was immediately thrown in with a very diverse student body.”

Although students in New Haven may not have been similar racially, ethnically, or socioeconomically, they did have one thing in common. “Yale was really academically challenging. It can break you down, or you can thrive on it,” said Knobel. “I thrived in that. It was not for the faint of heart…I had never been around such homogeneously, self-confidently smart students.”

Knobel said he especially enjoyed the Yale “house system,” wherein students were divided into residential colleges within the university itself. This provided “kinship” and “camaraderie” among students and faculty in the form of intra-house bonding, since members of each house would dine and socialize together.

He graduated cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa from Yale in 1971 with a B.A. with honors in History and pursued graduate school. He married his high-school sweetheart Tina two weeks after his graduation.

Of his decision to go into teaching, Knobel credits his favorite uncle, who was “a small college history professor for his whole life.” This uncle was especially interested in the history of the American Civil War. Knobel claims that his travels with this uncle to visit civil war sites before they were a part of the National Park system drew out his yearning to engage the field professionally.

“He got me interested in the past in that way,” he said. “I probably knew from the beginning that I wanted to be a professional historian.”

Knobel went on Northwestern University, where he received his Ph.D. in History in 1976. “I enjoyed Northwestern; I came to love Chicago,” he said. “I enjoyed Evanston and the North Shore.” His first child, daughter Allison, was born there in 1974.

He was hired as an Assistant Visiting Professor at Northwestern immediately after his graduation, though he soon began looking for jobs around the country.

“Texas was awash with oil money in the late 1970s,” said Knobel, and many large state schools were hiring huge amounts of new faculty. Knobel himself was hired at Texas A&M University in College Station alongside five other historians in 1977. He described the school as a “large, public research mega-university,” whose student population would grow by 20,000 in the 19 years he would spend there.

“We made that home,” he said. “I had a rewarding career there for 19 years.”

He started as an ordinary history professor and taught in large settings “of 200 at eight o’clock in the morning,” although he also had chances to “teach small classes and teach graduate students.” He served “exclusively in the classroom” for the first “ten or twelve” years. He also wrote two books on history during this time – Paddy and the Republic in1988 and America for the American in 1996 – and co-authored a third, Prejudice, in 1982.

Knobel’s experience was changed through the development of the Honors College at Texas A&M. “They really needed an honors program to provide maybe the most ambitious students with greater access to professors and to the small, participatory classes we take for granted.”

This is how Knobel wound up in administrative work. “I was teaching and leading this program which was kind of a small college the size of Denison, a couple of thousand students…with its own residence halls, with its own faculty.” He became Dean Director of the Honors Program, then Associate Provost for Undergraduate Studies by the time of the end of his career at A&M.

Knobel then returned to the liberal arts curriculum entirely. In 1996, he was asked to begin serving as Provost and Dean of Faculty at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas, outside Austin. Southwestern is the state’s oldest liberal arts college.

“It, along with Trinity University in Texas, are the leading liberal arts colleges,” Knobel explained, comparing their rivalry to that between Denison and Kenyon.

“Southwestern approached me and said, well, you’ve been trying to simulate a liberal arts college like this within a public research university through the honors program,” he said, “which was true. In the back of my head, actually, was Denison, as I tried to evolve this college within the university.”

“I was pleased that in all these rolls I continued to teach,” he added, emphasizing his profound interest in both writing and teaching history.

Knobel stayed at Southwestern for three years. “Just at the end of my second year I was approached by Denison and the search firm it was using” to find Myers’s successor, he said. Originally, Knobel was not interested due to a great affection for Southwestern and Texas. “They continued to press me, and I said, okay, I might be willing to share my resumé, but there’s something that they’d probably forgotten about me, you know – how am I going to explain to the Board of Trustees and the search committee that I was a Denison student once and didn’t stay?”

Eventually, Knobel agreed to an interview. “I guess I was what they were looking for. In fact, I have come to believe that the Trustees and the search committee thought it was sort of an asset – that I had spent time here but wasn’t a graduate.” He continued, “I didn’t quite have an alumnus’s rose-colored glasses…but yet, I would know the place in a way that others might not.”

Knobel began his tenure as the nineteenth President of the University in 1998.

The people’s president

Knobel’s governance of the University would see numerous changes to the campus, to the student body, and to the academics of the school.

“I think what jumps out to people’s minds, particularly the minds of many of the alumni, are the physical changes that have come to campus,” he said. Over his 15 years, over $250 million dollars worth of construction has taken place on the Hill; between Knobel’s time as a student in 1968 and his arrival thirty years afterward, only three buildings had been built (Burke Hall, a library addition, and Olin Hall of Science). “We really had a facilities deficit.”

Knobel charged the school with the construction of a huge expansion project. Residentially, this included the Brownstone Apartments, the Sunset Apartments, and renovating Chamberlain. Academically, Knobel oversaw the construction of the Burton D. Morgan Center, Samson Talbot Hall, and the Slayter garage complex. He also renovated or made significant additions to Ebaugh Hall, the Mitchell Athletic Center, and the Bryant Center for the Arts (formerly Cleveland Hall). Although he agrees that many may remember these projects as a “keystone” of his presidency, he hopes it will not be the “primary” focus.

Knobel said what he most wants his presidency to be remembered for is “things having to do with people.” Specifically, he highlights three groups of people: students, faculty, and alumni.

With regard to student makeup, Knobel explained that there have been several important developments. “Over the last fifteen years,” said Knobel, “we have measurably improved the academics of the student body. Denison’s always attracted many good students, but [in] some earlier parts of its history, the student body had a long tail in terms of the academic preparations and credentials, and we’ve raised that tail, so the whole student body has upshifted.

“And,” second, “simultaneous to that, we’ve been able to enroll a much more representative student body. Probably the one that most jumps out at everyone is race, because it is visible, but also internationally, the international student has grown, certainly socioeconomically as we’ve invested such large proportions of our resources into scholarships and financial aid.” Knobel also stressed greater diversity in terms of “faith backgrounds, in terms of the kinds of communities and schools people come to Denison from, and geographically. We used to be thought of us as primarily a northeastern university…but now we are increasingly California, Arizona, Florida, the Carolinas…so we’re more national and international at the same time.

“This is a great thing for education,” he said. “You want the person in the seat next to you to not be just like you” in a small classroom setting. “It’s also great in terms of campus life, although sometimes we don’t appreciate that. There’s such opportunity to learn from one another on a residential campus.”

“We share an experience here, but we really don’t want to be all alike,” he said. This increased diversity, Knobel added, “has made Denison a sounder institution of higher education.”

Another enormous development has been “investment in faculty. We’ve grown the faculty significantly,” said Knobel. When he arrived at Denison, the student-to-faculty ratio was 12:1 to 13:1. During the last 15 years, Knobel has driven this down to 10:1. This, he said, “would not only keep classes small” but allow for greater one-on-one interaction between faculty and students. Knobel stressed that this is a difficult task because of the sheer number of new faculty necessary to lower a faculty-to-student ratio by one digit. When Knobel was inaugurated, Denison had little over 180 faculty members; it now boasts over 220.

As parts of this program, Knobel’s administration reduced teaching loads, allowing them to focus on more on research; significantly boosting faculty salaries to retain talent; enhancing faculty research grants and opportunities.

As a third achievement, Knobel said that “we re-energized the Denison alumni community.” He explained that although alums have always “been loyal,” the “decision made…to change the role of Greek life on campus” by President Myers, a few years before his appointment, had complicated alumni relations. “It cut both ways. It was certainly disconcerting to some alumni; to others, [it was] much celebrated.”

“It was necessary to re-engage all these alumni and re-engage their financial support,” he said. He added that his administration needed to manage the college’s finances “efficiently, to grow the endowment.”

Knobel agreed that there were some pivotal moments in the college’s recent history. He highlighted the aggressive endowment-enhancing campaign between 2005 and 2008 that enabled his administration to affect many of its goals such as growing the faculty and physically improving campus. He also said that laying out the “strategic plan” between 1999 and 2001 was an important step in actually concretizing the Board’s vision for Denison. “That plan said we had to make progress on a whole bunch of different fronts.” Knobel also said that the decision in 2001 to develop “apartment-style housing for seniors” was critical to improving residential life. Previous to that, only Stone Hall had offered apartment-style living. Knobel said he was “hard pressed” to think of another college in the country that offers the kind of “graded” living system Denison is now able to offer to its student.

With regard to the 2007 Mitchell discussions, sometimes referred to as “riots,” Knobel said that while such incidents are “sometimes dramatized,” they are part of larger historical and sociological trends. “That was a time when the community did come together and say, ‘Whoa, we’ve been patting ourselves on the back with having achieved much greater proportional diversity,” he continued, “but are we making use of that? Are we respecting one-another…are we listening to one-another?’”

“A continuing work”

Knobel will enter retirement on July 1st of this year. He and his wife plan on returning to their family in Georgetown, Texas, near Southwestern University. “The thing that’s taking us back is our grandchildren.” The Knobels have two grandsons, Grant Matthew and Connor, who are four and five-years-old, currently being taken care of by Knobel’s son-in-law after the loss of his daughter Allison, their mother, to breast cancer in 2011.

In addition, Knobel plans to “return to [his] work as a historian and go back to writing.” He has asked architects of his new home in Texas to build a study that he can use for writing and research, which he left on hold as president. He also foresees doing some “part-time educational consulting work.”

Finally, Knobel plans to spend some time with his wife and do some international travel. He cited Italy, southern France, and China as possible destinations.

Dr. Adam Weinberg will assume the presidency in July 1.

“His first task,” Knobel said, “will be to work with the campus community to develop a new strategic plan. We took that plan we started on early in my time and pretty much did all the things we said we wanted to do…But his charge will be, let’s take the next ten or fifteen years out, what’s the plan forward? And I think what he’s discovering already, and I think what the Board of Trustees sees, the last plan was all about building us up across the board. We’ve done that. The new plan can probably be more focused on two or three big ideas…I don’t know what those will be.”

Knobel concluded with two rhetorical questions. “We do know that he will come to us with his current experiences as president of World Learning with a real interest in internationalization. How do we prepare students, wherever they come from, for a world that’s shrinking?”

He also hinted that the work of diversification, that work which drove him to pursue Yale those many years ago, is not yet complete. “How do we encourage people to more than respect one another, how do you encourage people to interact with and respect one another?”

The answers to these questions are in others’ hands now.

*

The Denisonian staff would like to sincerely thank Dr. Knobel for his service to the Denison community, and wish him the very best for the future.