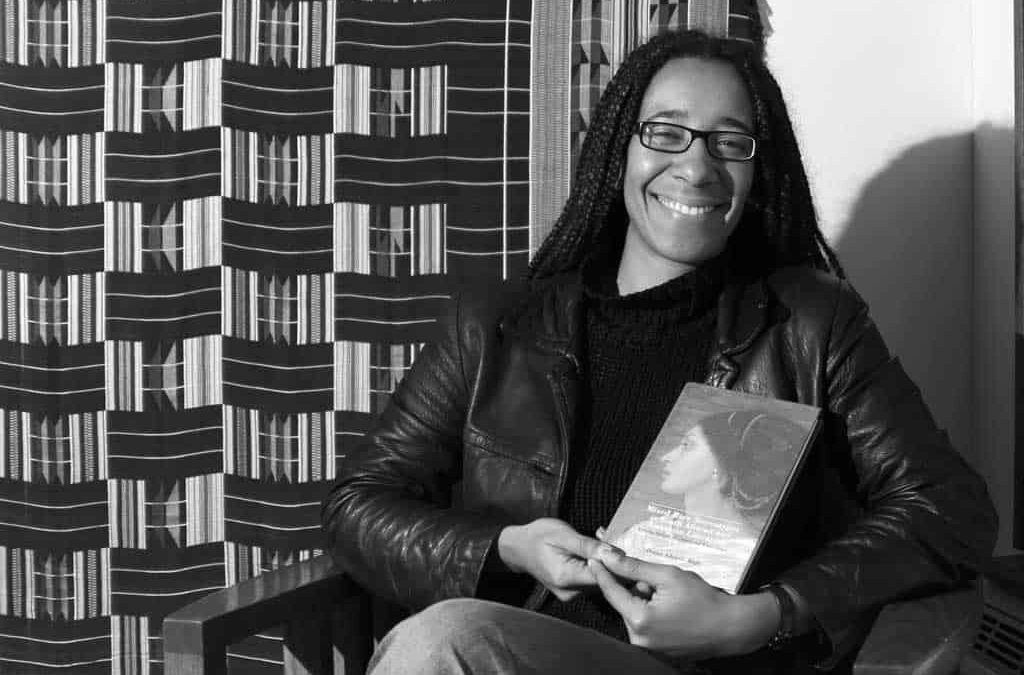

The United States is undoubtedly one of the most – if not the most – racially diverse country in the world, and seven percent of American children born in the last decade were bi- or multiracial. Denison English professor Diana Mafe, a Canada native, has a new book out that explores literary representations of biracial blacks in the United States and South Africa titled, “Mixed Race Stereotypes in South African and American Literature: Coloring outside the (Black and White) Lines.”

Mafe’s book, which was published earlier this month, is a 150-page examination of feminist and queer theory as it applies to the American “mulattos” and the South African “coloureds,” different terms for the same subject: biracial children who are the offspring of black and white parents.

The first 40 pages or so act as both a history lesson and introduction to the topic. She describes how mulattos and coloureds came to be – through consensual and nonconsensual sexual relationships between white men and black or African women as a result of colonialism and slavery.

Mafe outlines the historical stereotypes of the mulatto, which translates to “mule” in Spanish. Like a mule, the mulatto was assumed to be a weak, infertile product of two different species. The stereotypes grow deeper depending on the gender of the mulatto. For women, who Mafe differentiates as “mulattas,” they are represented in art and literature as beautiful and sexual, whereas the men are depicted in some literature as “not heterosexual enough” and a symbol of “sexual ambiguity.” This is attributed to “the mulatto race [as] a female race by virtue of its inferiority, [and] the gender distinctions within that race begin to blur.” As a result, queer theory has been applied to the study of mulatto men in literature.

Anyone familiar with the mulatto tradition in American literature should know the archetype of the “tragic mulatto,” a theme analyzed throughout Mafe’s work. Represented in both American and South African literature, the tragic mulatto is typically a beautiful biracial black woman who is mentally disturbed and feels as though she is on the outskirts of society. Mafe quotes early-20th century sociologist Edward Reuter who said, “…the mulatto is an unstable type… Nowhere are they accepted as social equals.”

On the other hand, the mulatto man uses his racial ambiguity to combat white patriarchy. Mafe argues that this literary tradition is embodied by the political ascent of President Barack Obama, in that he was able to cross racial lines and defeat one white man (John McCain) and replace another (George W. Bush).

The book serves as a Venn diagram, comparing and contrasting South Africa and the United States’ response to mulatto populations. One of the largest differences is the old American legal concept of “the one-drop rule,” which decided that the smallest fraction of black ancestry meant that a person was black. Mafe quotes novelist Sarah Gertrude Millan, who wrote in 1927 that “In South Africa, a drop of black blood is […] ignored. In America, it is hunted out.”

The literature under Mafe’s critical gaze also showcases two sharply different perspectives from two different centuries on what makes the mulatto “mad.” In Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre”, Rochester’s wife Bertha is mentally ill and “racially suspect,” writes Mafe. There’s no context to her madness in the 1847 novel; her mental state, like that of other mulattos in literature, is considered to be a given. However, in Jean Rhys’ prequel to “Jane Eyre,” “Wide Sargasso Sea,” chronicles Bertha’s life before her marriage to Englishman Rochester, and it shows the reader, through a 1966 post-colonial lens, that Bertha is not crazy because she is a mixed-race Creole; she’s crazy because society has marginalized her as a result of her mixed-race heritage.

Today, the mulatto literary trope continues to be popular. Mafe asserts that this is because the “mulatto embodies infinite binaries.” And, she’s right. What better character type to navigate right and wrong, good and bad, black and white, than a character who literally falls in the middle?

If you’re searching for a better understanding of race and how it is truly a social construct, Mafe’s book is a short, but informative read. The Women’s Studies department is hosting a reading of Mafe’s new book on Dec. 5 at 4:30 p.m. in Knapp 201.