By Kristof Oltvai, Editor Abroad

On a beautiful Prague afternoon some time shortly after Valentine’s Day, I had a choice: enjoy a semi-springtime walk around the city, or binge-watch the second season of House of Cards. I chose the latter, but really the show could’ve waited.

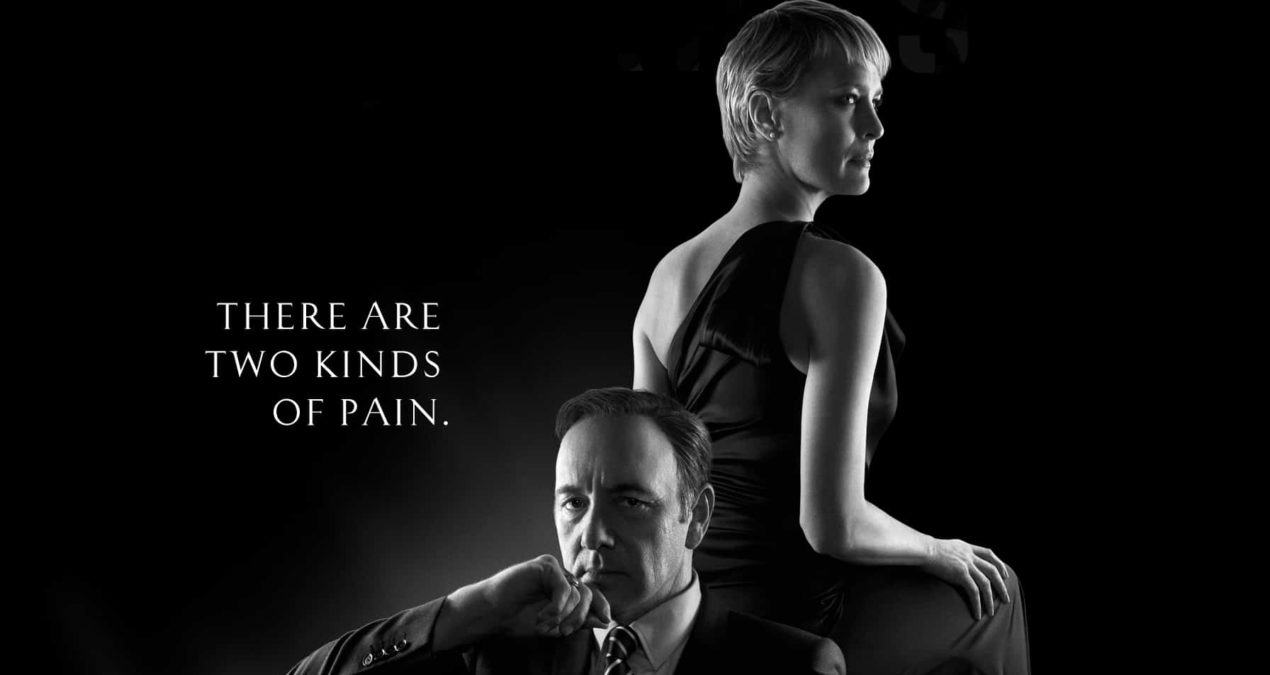

This is not to say that Kevin Spacey’s Machiavellian return to computer screens around the world is uninteresting. Indeed, the stakes are as high as ever. Spacey’s Frank Underwood assumes Vice Presidency in the first episode, and it’s not hard to imagine where his ship is sailing. The plot quickly takes on international dimensions as Chinese magnate-perverts enter the scene, and old enemies abound everywhere, from nubile reporter Zoe Barnes to the imperious Raymond Tusk.

The exciting setup dissipates quickly, however. Telling is Frank’s grisly metro-station murder of Zoe in the first episode, after which the writers find difficulty conjuring up good foils to the Underwoods’ slow-moving phalanx of vengeance. This is problematic considering the pantheon to choose from, but even big fish like President Walker, his Chief of Staff Linda, and newly elected House Whip Jackie Sharp fall for Frank’s Southern-drawl-drenched bullshit as quickly as I became exhausted with endless montages of one-sided negotiations.

And how endless it is! What is probably this season’s biggest failure is the bitter war – undoubtedly intended to be climactic – between Frank and Tusk that is drawn out for nine episodes (I counted). I lost my interest halfway through despite sentimental interludes about Frank’s Confederate ancestors or barbecue-man Freddy’s struggles in the hood.

What also hurts is that Frank’s confessions directly to the viewer, which draw in the audience and serve to embroil us in his schemes, are greatly reduced, if not in their frequency, then in their importance.

Whereas previously they explained the logic of Frank’s endless backstabbing and thus raised tension, in this season most asides have been subdued to brief philosophical quips about how stupid his enemies really are. While amusing, they’ve lost their key narrative function.

This is why the final punches comes a little out of the blue, and why Frank’s operatic victory seems somewhat hollow. There is much of the immorality, but little of the rage-filled pathos, that characterized the first season. Early on, Frank destroys a lamp in outrage, but that’s pretty much his emotional apogee this time around. For someone who found a decent amount of guilty pleasure, and maybe even a sprinkling of sympathy, in watching a slighted underdog undo his rivals one by one, the Underwood charm is quickly vanishing. You won’t find me begging for season three.