by Kristóf Oltvai, News Editor

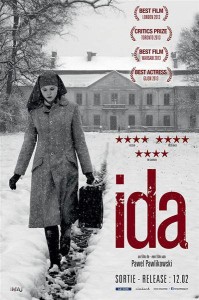

Few films strive to capture the silent, overwhelming omnipresence of deep personal faith in our secular age. But Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski’s Ida, just off the international festival circuit, not only tries — it succeeds. The result is a haunting experience.

When I first read its review in the New Yorker, I thought Ida would stumble in the worn-and-wearied trappings of the depressing Hollywood-Holocaust drama. A young woman, Ida, has been raised in a convent-orphanage by Catholic nuns outside Łódź. Before she takes her vows, however, her mother superior orders her to visit her aunt in the city, a chain-smoking alcoholic communist ex-judge and seductress who paraded in her glory days as “Red Wanda.” If Wanda didn’t soon reveal that she and Ida are the only surviving members of a Jewish family killed in the war, one might even think it the setup for some “odd couple” comedy.

What follows, however, is neither a comedy nor a sentimental piece on “rediscovering” one’s ancestry, although Wanda and Ida do get in a bouncy Trabant and set off to rebury Ida’s parents. Rather, it is the portrait of two radically different souls — the libertine and the mystic — who are forced to come to face with the realities of life and death.

Both women are exquisitely well-played. Agata Kulesza’s Wanda is a cocktail of existential angst whose two weapons against the world, a bottle of vodka and her friends on the Politburo, are wielded with surprising effectiveness. Her indifference toward Ida’s religiosity is complicated by her hatred for the everyman she claims to liberate the and small kindnesses dispensed toward favorites like a hitchhiking sax player. Wanda’s sensuality, cynicism, and her simultaneous love of the world’s pleasures alongside the bitter frustration in face of its absurdity make her relatable today.

Agata Trzebuchowska’s Ida is at once the stark opposite of and perfect friend for Wanda, although this latter truth is only slowly unveiled. While Trzebuchowska’s portrayal of shyness, nubility, and piousness were scripted, her theatrical genius lies in the ability to present an absolute plainness as the sign of deep inner life. Wanda and others repeatedly tell Ida how beautiful she is, but Trzebuchowska subdues herself so thoroughly it is only when she first removes her coif halfway through the film that we realize how true this is.

At the same time, though, we realize this beauty is untouchable and angelic, reaffirmed by Ida’s constant prayer. She prays in empty churches, on roadsides, by her bed, with peasants, always staring ahead, as if unmoved. And yet the trembling silence that pervades Ida’s interactions with others is only explicable through the logic of her own profound friendship with Christ. There is an important scene toward the end of the film when Ida mutters a few sentences to a statue of Jesus outside her convent at dawn, yet somehow we know she has been standing there all night. That is when we realize Pawlikowski’s achievement here is his ability to, somehow, capture the ineffable relationship between a human being and God on the silver screen.

Ida is not a movie for the faint of heart. And it is brief, a mere 80 minutes. But for those willing to watch the action onscreen, it unfolds like a little flower with many petals, whose scent is felt most strongly an hour or so after the theatre. Pawlikowski has indeed constructed an impressive meditation on love, death, and what is perhaps the fundamental challenge of human life: a challenge that is perhaps best encapsulated in those words from the Gospel of John. “But my Kingdom is not of this world.”