In a world that embodies social inequality and divide, art is a common escape. The freedom of creativity allows people to not only express their thoughts, but also encourages others to learn more about the ways of society.

One such artist who inherits inspiration from social injustices is Emory Douglas, a renowned revolutionary artist and minister of culture for the famous political party, the Black Panther Party.

The Denison Museum, in collaboration with the Department of History, has currently put his work on display. The exhibit is on display from February 5 to May 4 on the ground floor of Burke Hall, from 12 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday.

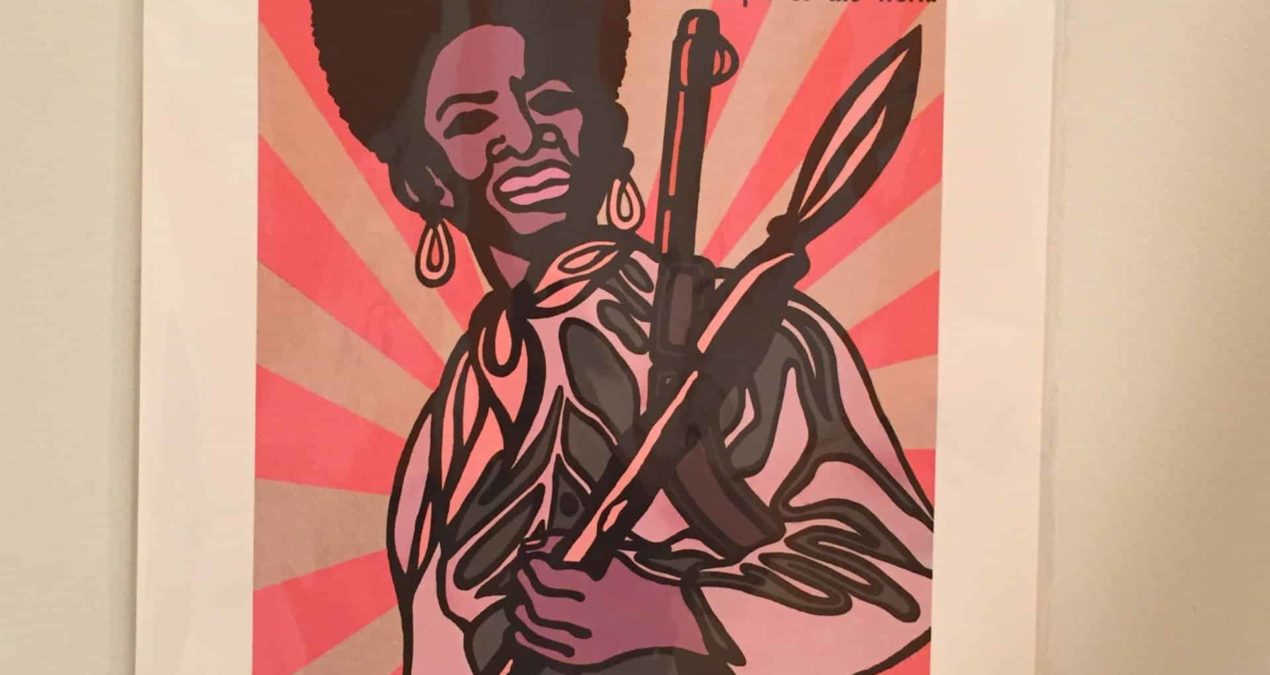

Douglas made his mark on American culture through his thoughtful and provocative work. He served as art director and lead illustrator for the party’s newspaper, for which he created widely distributed prints that now reflect American history and society in the 1960s and 1970s.

Much of his artwork consists of dark illustrative figures combined with text. The use of rhetoric as a creative device helps add powerful meaning to his work, which further highlights the struggles faced by the Black community even today. He’s trying to reach out to the larger public in general, instead of only targeting a particular group of people.

“I had to write a research paper on this exhibition, and coming here to see Douglas’s artwork was really inspiring. I liked how his work depicts really sensitive matters through powerful images, but somehow represents no form of hate towards anyone” said Emily Voutes ‘19, a studio-art and global commerce double major form Barrington, Rhode Island.

On February 21, 74-year-old Douglas visited campus to give an artist talk in the Denison Museum’s exhibition space. He spoke about how the central idea of his work represents the Black men, women and children in America all looking for fair access to housing, jobs and equality. His work not only illustrates, but empowers individuals and reminds us of the transformative power of art.

“Pardon me for being born into a nation of racists,” said Douglas during his talk, which to many is a bold statement that can be seen as the underlying message in work.

“His art is adaptable, fluid, and represents the everyday social injustices we often overlook. I’ve noticed how his messages shift from discrimination in the Black community to other problems, such as sexism and xenophobia, which are still persistent all over the United States,” said Voutes.