By Liz Anastasiadis, Managing Editor

NEWARK, Ohio — “I will never wait that long to look at my mail, I’m tellin’ you.” laughter filled the day room. “You can’t run from your problems babe, it’s not good.”

At The Main Place (TMP), a peer support and mental health recovery day center in Newark, Ohio, Tara Midkiff, a peer support staff member, tells jokes every Monday morning at Comedy With A Twist. It’s a group activity where she goes to TMP’s dining room and asks everyone to tell her something funny about their weekend — and if they’re serious, she tries to find the bright side.

The round, worn tables that crowd TMP’s kitchen are full of people. Some are clients and staff members; they sit together and listen to her story.

“My mailbox was so full that he told me to start payin’ bills,” says Midkiff. “I hadn’t checked my mail in a few months and man, was that a DIS-asTER.”

She joked about how she got into a depressive episode, which is why she kept on ignoring her mail. She would just let it pile in the mailbox and didn’t want to look at it.

“It was starting to make me feel hopeless, so I stopped looking. I had to remember that bills ain’t everything but still I can’t ignore them.”

She banged on the round table with the climax of her story and laughter followed — and continued to have everyone’s attention in the room.

“I think Comedy With a Twist is helpful because a lot of people are depressed and down about their situations,” says Midkiff. “When we can sit around and laugh about it, it eases the pain and takes some of the seriousness away.” Midkiff grew up in Newark, down the street from TMP. Her and her friends used to race past it when they were kids.

“That was the place for the crazy people,” Midkiff says. “No one wanted to go near it when we were younger. It was scary. Now, I think it’s the best-kept secret in Licking County.”

Midkiff has worked at TMP for three years. A mother of 6 kids, she has her hands full constantly with them and TMP.

TMP opens to the community every weekday morning at 8 am, and breakfast is served. Coffee and granola bars accompany a sign-in sheet for TMP to get reimbursed, tracking the number of people who use their services. At the beginning of the month, TMP doesn’t have as many visitors. It’s due to an influx of resources (food stamps, checks for disability, a few examples), at the beginning of the month due to government support. People are able to stay on top of paying their bills and using their food stamps. However, at the end of the month, these resources start to fall short and at TMP, people crowd the tables near lunchtime.

Phill, a regular client at TMP, always sits at one of the corner tables and observes everyone around him. During Comedy With a Twist, he reacts with the occasional laugh, running his large hands through his thinning gray hair. I sat down with him that day and started to talk to him about poetry and handed him a copy of Annabell Lee by Edgar Allan Poe that I had brought for a creative writing class I teach. Turns out, he was a huge fan of Poe, and he loved to watch thriller and horror movies with twisted plots. He read the poem to me out-loud while playing some Led Zeppelin from his android phone. I told him that he reminded me of my dad.

“Might as well have been brothers from another mother,” he said while he poured Mountain Dew into his mouth after I told him more about my dad’s love for horror films and classic rock. “I’d like to meet him someday.”

The Main Place is like a second home for Phill, and this is a common experience for other visitors.

Phill and I looked over, and Midkiff was standing animated, jumping and moving her arms in accordance with her story and audience. In that moment and forward, Tara reminded me of my funny and energetic aunt — blunt and realistic, but able to find the humor in everything in spite of her everyday struggles.

This, to clients and visitors to TMP’s Newark and Mount Vernon locations, is what the Main Place is to them – a family. It’s always there for them. TMP meets people where they’re at, not where they’re expected to be.

Peers become family. Family becomes support. And this is the foundation of peer support.

“A peer supporter is almost like a glorified life coach,” Midkiff jokes. “They’ve been through it all and now they’re here to help other people get through their issues too.”

TMP is a Peer-Run Organization (PRO). According to Mental Health America (MHA) as of May 2018, 45 states and the District of Columbia have established or are developing programs to train and certify peer specialists.

These specialists are day-to-day people — the peer support program recognizes peers who have extensive experience in a subject, and a large knowledge base that sets them apart from others. Current requirements to become certified are set by MHA and includes a current state certification with a minimum of 40 hours of training, a minimum of 3,000 hours of supervised work or volunteer experience providing direct peer support, and professional letters of recommendation.

MHA also collected evidence for peer support, and it was found that peer support lowers the overall cost of mental health services by reducing re-hospitalization rates and days spent in inpatient services, increasing the use of outpatient services. Participants who received peer-based services felt that their providers communicated in ways that were more validating and reported more positive provider relationship qualities compared with participants in the control condition.

Participants in peer support nationally have reported significant decreases in bodily pain, and significant increases in hopefulness.

The laughs in the surrounding day-room began to dissipate while the morning activity began to draw to a close. Midkiff went over to sit at our table and cracked a couple more jokes about her weekend before going back to her office.

Compared to a community mental health center, TMP offers a variety of services. Clients don’t attend their appointment and leave promptly. TMP is more personal. Someone comes in and TMP meets a lot of their needs, and help guide them so a client can choose if they want counseling, case management, a variety of classes that can be free or billed, or to just come to the center and socialize for a little and move forward at their own pace. This is the foundation of peer support and their community.

I stood up made an announcement in the lunchroom that my creative writing class was about to start. A few clients stood and we made our way to the art room.

I put my bookbag down at the front of the tables, which were connected edge to edge into a large rectangle and went to the chalkboard. Four others followed behind and found their seats around the table. None of them sat next to each other.

The prompt for the class: If you could make Newark into whatever you want it to be, what would it look like?

As soon as I wrote it down, Kevin, who had excitedly come in with his writing binder and pen, got up immediately and started to gather his things.

“Newark is a horror story,” he says and started to walk out of the room.

“You can make it whatever you want to be,” I interjected.

He stopped at the door, turned around and frowned at me. “No, thank you. I don’t want to be in this room.”

He wasn’t comfortable writing about Newark; he didn’t want to talk about it. A peer support staff member followed him once he left the room for a discussion.

Everyone else started to write for a half-hour. I wrote to them. Once everyone was finished, we sat together and shared our work.

Joe, a regular, shared, “I hope that one day, everyone can have free public transport… It’s so hard to get around here without a car.”

“I want a community where everyone helps everybody,” said Anne. “If everyone helped everyone, then people wouldn’t have trouble getting to work, taking their kids to school, they wouldn’t have debt. Everyone could be happy.”

When the class adjourned, one thing was clear — there’s a lot that people want change, and when inspired to envision it, they might move into action.

The circumstances of poverty can make it harder for people to get back on their feet. Without public transportation or a car, it’s difficult to get to work. If you can’t get to work, then you can’t afford somewhere to live, food to eat, and the list goes on. It turns into a cycle of relapse from recovery, whether that be mental health, addiction, or financial recovery. TMP tries to break that cycle with peer support, connections to other resources, and a community of understanding people.

TMP constantly has changed in clientele and visitors, people stay, and people go — people’s lives aren’t always consistent. But one thing remains open — the doors.

For those who live at The Place Next Door, an apartment complex located next to Newark’s TMP, it offers structured, permanent housing for adults with severe mental illness (SMI). About 70 percent of people who are chronically homeless experience a persistent mental illness, according to the Newark Advocate. It can be difficult for clients to recover while dealing with the obstacles of homelessness, and The Place Next Door offers permanent housing in apartment-style living for up to 10 people with SMI.

“Being homeless, a lot of times, people that will let you stay with them do drugs. So, they have no choice really. They’ll be a couple of days clean and lose their spot at the Salvation Army and go get high. Homelessness is a big hinder for recovery for a lot of people,” says Midkiff.

According to a 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 7.9 million people in the U.S. experience both a mental disorder and substance use disorder simultaneously, otherwise known as a dual-diagnosis.

According to the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI), a dual diagnosis, also referred to as a co-occurring disorder, is a term for when someone experiences a mental illness and a substance use disorder simultaneously. Either disorder—substance use or mental illness—can develop first. People experiencing a mental health condition may turn to alcohol or other drugs as a form of self-medication to improve the mental health symptoms they experience.

According to the Behavioral Health Evolution, symptoms of mental health disorders can be masked by the usage of drugs, and symptoms of mental illness can mask drug usage.

At TMP, co-occurring disorders can be addressed through anger management, addiction and anxiety/depression classes, therapy, peer support in classes and at the center, and clients expressing themselves in creative writing and art classes.

If you don’t live at The Place Next Door, TMP can help pay for housing. Clients can work with case management to eventually obtain their own place. It’s a 7-step process, starting with an intake, which is a process in which the client’s information is put into TMP’s system and then, connected to resources in the area. Next, a client assessment, to initial meetings with case management, a housing assessment, another meeting if they’re qualified for housing with the housing director, and the last step is to receive their voucher for housing. After this process, the client has to find a landlord that will accept the voucher. The client pays rent that’s based on 30% of their income, and TMP supplements the rest.

“The Main Place changed my life… I was in a really dark place when I came here and now it’s considerably brighter, and I have a place to live,” says Phill.

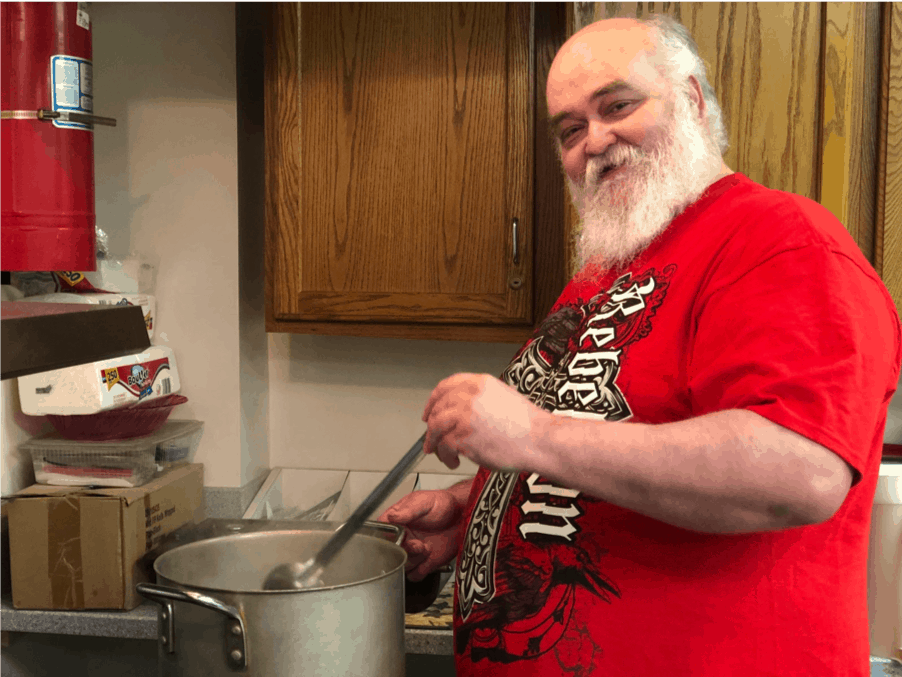

He brushed aside his greying hair from his forehead with his elbow and sighed as he breaded fish in the kitchen for lunch that day. Phill was just recently hired as the new cook after the other one quit last week. He picked up lettuce and chopped it quickly with skill and a smile on his face.

“My furniture came in today,” continued Phill. He started to chop potato wedges to put in the oven. “And I have a job… I love to cook and didn’t think that I would get a job doing it.”

His blues eyes crinkled around the edges at the thought, and he looked down and continued to chop onions, tomatoes, and fresh herbs.

“I was sleeping on a mattress on the floor, but I just couldn’t sleep last night, I was so excited to get the furniture… I want to invite my friends over for a movie night.” He currently lives alone.

Phill is now in a stable situation because of TMP’s resources. His life is stable. He can focus on his life without worrying if he’s going to have somewhere to sleep, something to eat, or keep his job. Feelings of hopelessness, trauma, difficulty with recovery and poverty can be perpetuated by social context.

According to Bruce Alexander, a psychologist and professor emeritus from Vancouver, BC, Canada, fragmentation leads to dislocation, and dislocation leads to addiction. He discovered his dislocation theory for addiction. Dislocation is another word for radical social isolation. Humans, as social beings, don’t react well to social isolation and therefore, can turn to additions to lessen the pain of isolation, fear, and hopelessness.

Alexander’s dislocation theory challenges the stigma surrounding addiction and mental health by stating that it isn’t the drugs that cause the addiction, but the social context. Addiction in this theory is socially conditioned by the environment, surroundings, and a person’s socioeconomic context.

When people are scared, lonely, fearful of their future, bored, and isolated, the pain can manifest into and feed addiction.

“We forget the human piece of it — they’ve gotta believe in wanting. In my anger management class, there’s a lot that focuses on things that aren’t anger,” says Liz Sutherland, social worker in residence at TMP. “It focuses on loneliness, feeling alone in the world, hopelessness, all those feelings that are down there and clustered and it isn’t hard to get angry because at least you’re feeling something that you can identify.”

For at least nine out of ten clients at TMP — it’s about recovery from all kinds of trauma.

The Main Place is a family, it’s support, and for some, it’s a help for those who have no other options. People come back after their recovery to become peer support specialists or to simply hang out. All are welcome at the center.

When I walked into the lobby to say goodbye to the desk receptionist, Faye, for the day, a loud voice suddenly erupted from one of the three public-use phone rooms. It was Kenny who just got off the phone with his parole officer. The door slams open, and he sprints out and screams f***. He ran around the day room for a few minutes with his hands up in the air, almost as if in surrender to his circumstances. Bunching his fists, he exited to the outdoor sitting area with his pack of cigarettes.

I looked to Faye and she laughed, hands thrown up in the air, another hand clutched her stomach.

“Don’t give him no mind,” she says in a thick Bronx accent, waving her hand. “That’s just Kenny. He don’t hurt nobody.”

He sat on the bench outside alone, talking to no one. Kenny, and everyone, deserves to be met where they’re at. No matter what. Without judgement.

He lit another cigarette, took a deep, long drag, and continued his endless conversation with himself between puffs. The embers of his cigarette glowed with each inhale.

Teaching classes at the Main Place made me realize something about everyone who uses TMP’s services: once someone is told they can pursue their dreams after being discouraged for most of their lives, people will start to envision a new path. As long as they believe in themselves, they believe in the future. If surrounded by family, by peers, and by friends, hope starts to grow. Eventually, that can lead to recovery.

When Kenny was finished, his thin, long fingers snuffed it out on the bench, dropped it on the ground, and large, worn boots stepped in its ashes as he slowly started to stand.

“Can you see it?” he said to me and pointed to the bench when he

came back inside. “I showed that cigarette who’s boss.”

EDITORS’ NOTE: Throughout this article, pseudonyms are used to keep the identities of individuals confidential.