A small town. A lonely man. A lonely woman.

While these three fragments may encapsulate the essence of Will Eno’s “Middletown,” the play is about so much more. Tearing past the trifles of a complex plot and other possible distractions, the play confronts its existential themes directly, and a skillful cabal of Denison’s theatrical finest brought the philosophical questions to life for this reviewer on Thursday night.

“Middletown” features an ensemble set of characters representing a cross-section of the citizens of the eponymous town, but focuses mainly on two: Mary Swanson, a pregnant newcomer with an absentee husband, played by Sara Blike ‘15; and John Dodge, an awkward handyman who struggles with loneliness, played by Marc Andre Weaver ‘17. Others included veteran Chris Morriss ‘14 as the homeless alcoholic Mechanic, Pearse Handley ‘14 as the hard-nosed Cop, and Emily Smith ‘15 as the doting Librarian.

Two major dichotomies operate in the story. The first is between life and death. Mary, as an expectant mother, nervous but hopeful, is played off against the failing John, whose anxiety and depression eventually drive him to attempt suicide.

The second conflict is between the apparent hugeness of our own everyday problems and the vastness of time and space. What do our own personal struggles matter when they are lost to history, as contemplated by Annie Tracy ‘15’s Tour Guide and her two tourists, Maddie Johnston ‘14 and Matt Harmon ‘16; or to the immensity of the universe, as suggested by Middletown’s very own astronaut (Aleksa Kaups ‘16) who looks down, godlike, on the world?

The script, a kind of blending of “Our Town” and “Waiting for Godot” (although I drew parallels with Denison’s own “Legacy of Light” and the film “Cloud Atlas” as well), confronts the audience head-on with the absurdity of presenting theatrical constructs as representations of reality. Characters break the fourth wall several times, and one scene preceding the intermission even doubles the audience, prophesying its reactions.

All of the students were superb in their roles, and well-cast: the proud, Aryan Handley as a tough patrolman; the gruff, masculine Morriss as a pseudo-animalistic degenerate; the bespectacled Smith as a kindly clerk. But, no offense to these veterans of Denison’s many stages, the spotlight was stolen by the nubile Marc Weaver as John Dodge.

The range of emotions explored by the John character aren’t the shiniest aspects of the human experience. John starts lonely and depressed, progresses to attempted suicide, and concludes his on-stage presence in the death throes of a self-inflicted infection. And yet Weaver acted through all these scenes in a way befitting a professional thespian. I was nearly moved to tears at certain points near the play’s climax, when John struggles to express a fierce desire to live despite his attempted suicide.

Simply put, Weaver was engrossing. It is rare to see an actor bring a character to life in such a natural and tender way, and to know that this talent is coming from a first-year student, a newcomer to Denison’s stage at least, is exhilarating. Seeing by the playbill Weaver is an aspirant theatre major, and his return to the stage is much-anticipated. I especially look forward to seeing Weaver pull off the same level of immersion with different kinds of characters.

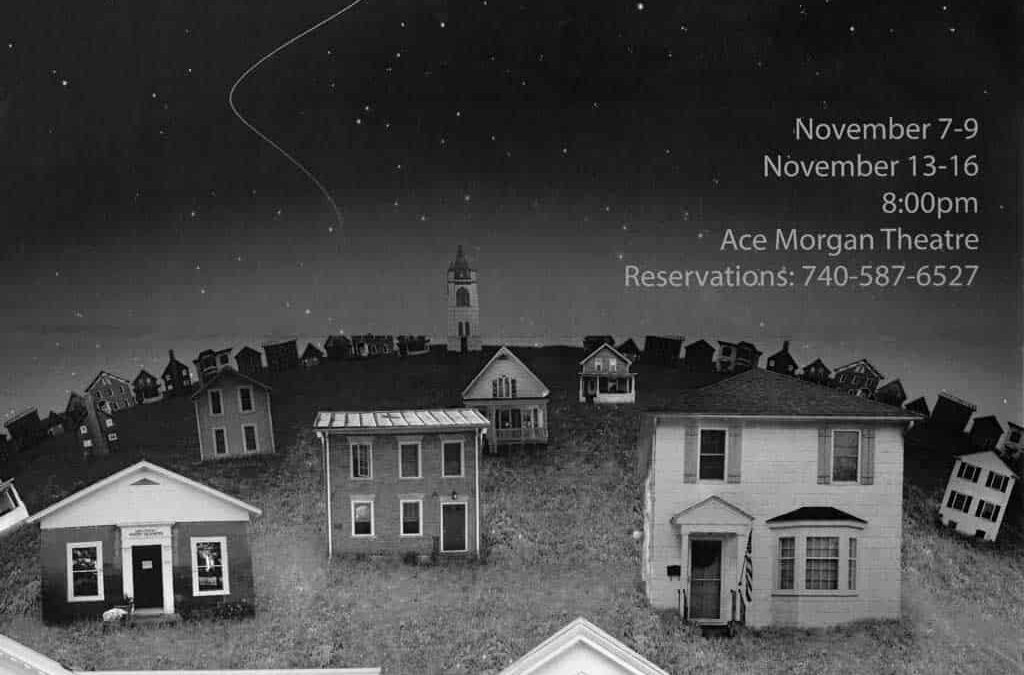

“Middletown” is still playing this week! Though not exactly the most uplifting of stories, the ambiguities and major questions addressed by Eno merits two-and-a-half hours of one’s time. You might not leave with a desire to conquer the Indies, but you’ll certainly have learned about what it means to be a human being.