ELLIOT WHITNEY, Contributor—

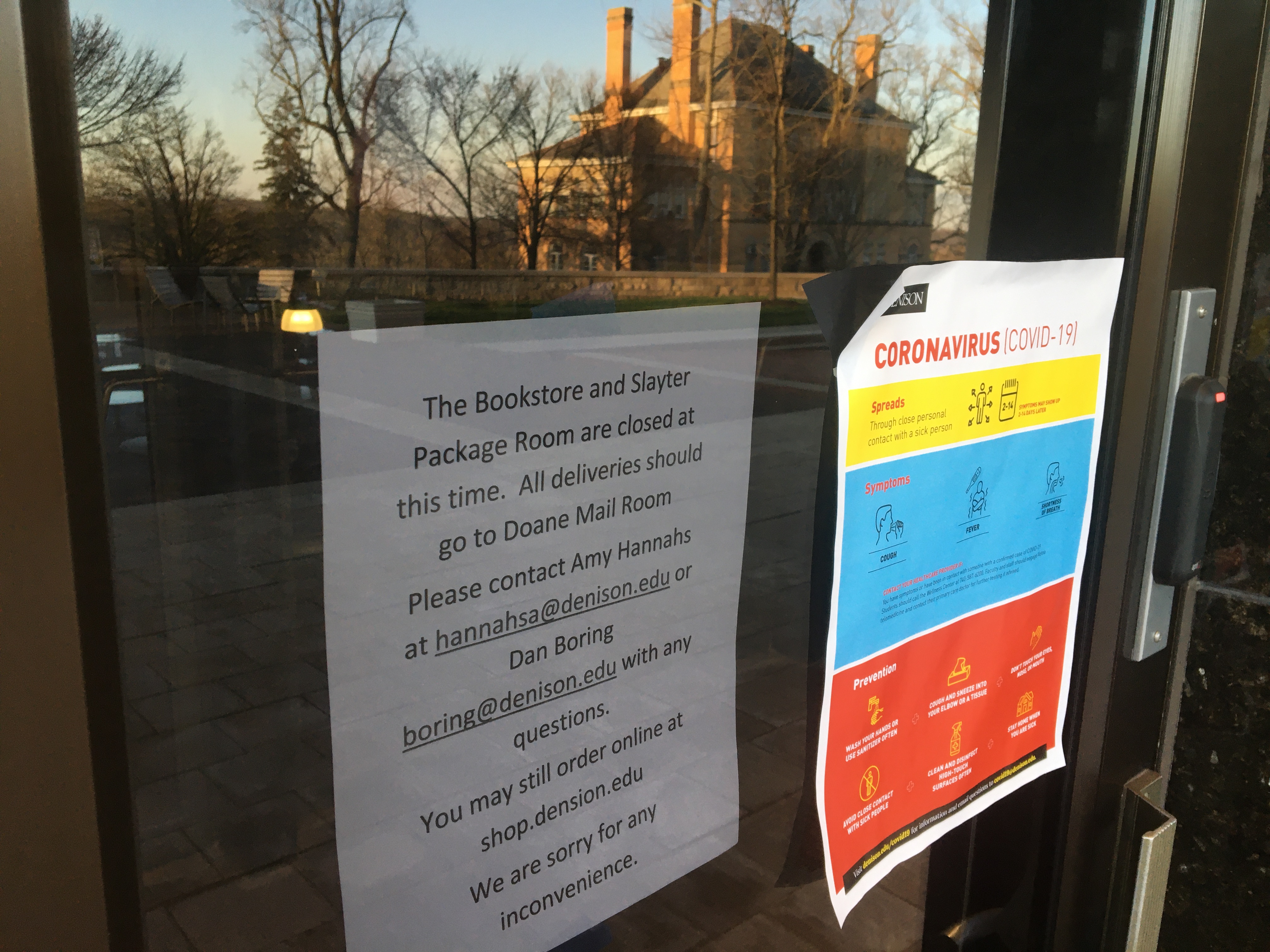

Over the past year and a half, universities across the country have been grappling with the issue of bringing students back to school during a historic global pandemic. March 10, 2020, Denison University students received their first “important community update.” Little did they know, these would become standard protocol for the next couple of years.

The middle of the email read, “All students are expected to leave campus by Monday, March 16, through at least April 3. There is a very real possibility that we will extend remote learning through the end of the semester, therefore we strongly encourage students to take all of their belongings if at all possible, and especially all items and materials they need to continue their studies remotely.” This caused a campus wide eruption of chaos and speculation. What would happen next? Would we be back in three weeks to resume classes and normal life? Many students left their rooms half full hoping their return to campus would come soon. “In March, I never thought that the coronavirus was going to send us home for the entire spring semester,” says senior Lily Pigott, 21, psychology and communication double major from Massachusetts, “let alone dictate the course of the following year as well.” After the Hill emptied out that weekend in March, it would not be full again until five months later.

Unlike Kenyon College and Oberlin College, two of Denison officials’ confidants throughout this pandemic, Denison welcomed all students back to campus in August 2020. “I spent a lot of time on the phone with my counterparts at Kenyon and Oberlin,” says Denison University President Adam Weinberg. “I have a ton of respect for them. We just ended up making different decisions and for each of us, those decisions were the right ones for our institutions.” After months of deliberation and planning, students were granted the option to return to campus for a year of hybrid learning.

The decision to return to campus was not an easy one. “We made a really different decision than other colleges,” Weinberg says. “Early, early in April, I pulled together a cross-organizational team and I said, ‘Your charge is to open campus in the fall. I don’t care what it costs, I don’t care if we are the only college in the country that’s open, we’re going to bring people back,’” Weinberg says. The Denison administration was eager to bring students back on the Hill from the moment they left. “When I heard we were all invited back to campus, I was super excited and confident,” says Pigott. “I had personal concerns about leaving my family during a pandemic, but I was ultimately convinced by my confidence in the Denison administration that I would feel safe isolated on the Hill with my peers.” That summer of 2020, students anxiously awaited President Weinberg’s email updates with information about the terms of the Community Care Act, a document that all students returning to campus were required to sign, and hoping that the COVID surge wouldn’t strip them of their chances of returning to Granville.

Returning to campus amid a global pandemic was anything but ordinary, but the Denison administration worked to replicate the most normal campus experience they could. “This is a really formative time in our students’ lives, and Denison is an important place for our amazing community of faculty and staff who work here. So our North Star has always been: How do we manage COVID risks while still fulfilling our mission and purpose, and taking care of our campus community broadly?” says Alexandra Schimmer, Vice President and General Counsel at Denison University. Serving as General Counsel, Schimmer brings the legal dimension to the establishment of Denison’s COVID guidelines and protocols. “Lawyers are also used to thinking about risk three-dimensionally. In COVID terms, this meant, foremost, accounting for health and safety, but also the other risks and implications of our decision-making,” Schimmer says of her role at Denison. “The question/goal for us is how do we give our students as normal of a year as possible while also minimizing the risk of an outbreak,” Weinberg echoes. “That’s what we’re trying to do.”

Both Weinberg and Schimmer emphasized how fortunate Denison was to have dedicated staff, faculty, and community members to make this return to campus “far from perfect, but pretty good,” as Weinberg says. “I knew our faculty would step up and find a way,” Weinberg explains. “There’s not a faculty in the country that cares more about their students than this faculty.” Many students felt that. “They’re very supportive,” says Pigott. “I often think about the risks they are taking in teaching all in-person classes, but they seem ok with it, like they want to be here.” For the fall semester in 2020, Denison gave both students and professors the agency to complete courses either in person or virtually. Only a few hundred students didn’t come back to campus for the fall semester and were able to complete courses from home. Students were still not required to return to campus, but classes conducted in the spring semester of 2021 were not required to have virtual abilities. This meant that students’ class selection was limited to their geographic location and there was no guarantee that students who were on campus, but were sent home for breaking COVID guidelines, would be able to finish their courses. This year, students and faculty are all asked to be on campus and there are no longer remote class options.

This transition back to fully in person living and learning was one that demanded extensive behind-the-scenes planning. According to President Weinberg, the most important part of creating a strong and sufficient response starts with asking the right questions. “In a period of ambiguity, you at least have to get the question right, because if you don’t get the question right, you’ll never get the answer right,” Weinberg explains. “For me, the question was really simple: How do we stand by our people? That was it.” In crafting an answer to this central question, the Denison Administration engaged in many conversations with other university presidents. “There was more conversation between college presidents in the first eight or nine months of COVID than I’ve ever seen in higher education,” says Weinberg. That being said, Denison mainly employed the help of medical resources made available by the Ohio State University. “We’ve been super fortunate, because we’ve been working closely with this team of research scientists and epidemiologists at the Wexner Center,” says Weinberg. “We’ve had access to really good, strong experts, and a lot of colleges don’t have access to that.” Living just 35 miles down the road from Columbus, Denison followed closely the information and recommendations offered by experts at the Ohio State University, much more so than other, more similar, small liberal arts colleges. ““All along, we’ve been guided by an expert team of scientists and epidemiologists from Ohio State. They have been great partners to Denison,” says Schimmer.

The costs of COVID tests are one aspect of the COVID protocol that have changed over the course of the last year and a half. During the 2020-2021 academic year, Denison administered weekly signal COVID tests in which students were selected at random for testing and had rapid and PCR tests available for other symptomatic students. These tests were of no cost to students. This semester, fall of 2021, students were required to produce a negative COVID test within four days of their arrival to campus and haven’t been tested since unless they were symptomatic or contact traced. The responsibility now falls on students to self report any symptoms and to make appointments for testing through the Whisler Student Health Center. Students who are symptomatic first receive a rapid test, which, if positive, have to self isolate, and if negative, students are required to also produce a negative PCR test result. These two tests, administered by Denison faculty, amount to an $110 charge for students. Even though Weinberg says, “Students have been great. We’ve been getting a lot of people coming in,” many students are concerned that this fee will dissuade their peers from making the decision to get tested if faced with COVID like symptoms. “I’m trying to put this in an email for next week but insurance should pay for it and if it doesn’t, students can apply for red thread grants,” Weinberg says. “We don’t want finances to be a burden in the way of getting tested.”

It wasn’t so easy for senior Lily Pigott. “I didn’t want to get my roommates, my classmates, or my professors sick,” says Pigott. “But I felt kind of deceived because I figured from the emails that testing would be more accessible than it was.” Pigott called the Whisler Center when she started showing symptoms and had a phone call appointment to determine if a test was necessary. They found that it was necessary and scheduled Pigott for a rapid test the next day. “I assumed since Denison had the means to give out thousands of free tests last year, we would have the same resources this year,” she explains. The nurse at the Whisler Center told her she could either file a personal claim to her insurance company or get tested at an off-campus testing site that accepts insurance. “I felt obligated to get tested at Whisler,” says Pigott. “There were no testing options for three days in Licking County and I had already admitted to myself, the nurse, and my friends that I needed to get tested.” Pigott remembers feeling uncomfortable with the off campus testing option because it made her feel as though “they weren’t following the numbers as closely as they should be.” “I was really aggravated with Denison,” says Pigott. “I am lucky to have the means to pay for it, but a lot of people don’t. I was also upset because my mom works hard for me to have health insurance and be safe and I felt bad putting her out because I was feeling sick.” The financial pressure that Pigott felt was just one microcosm of a much larger nationwide financial crisis since the pandemic began. Testing, treatment, quarantine, all parts of the COVID process cost money on some end, either the individual is paying out of pocket or the institution has systems in place to take financial responsibility for their community. “Since the pandemic, there is such a stigma around feeling sick because people are rightfully scared,” says Pigott. “There’s an uncomfortable feeling walking around campus and you want to make yourself and others feel more secure and paying $110 didn’t help with that overwhelming feeling.”

While COVID rates remain low among the highly vaccinated Denison population, the threat of COVID has hardly been eradicated on the Hill. According to the Denison COVID-19 web page, 99% of students and 95% of faculty and staff are vaccinated; even though these rates are high and positive COVID tests are relatively low, there is still COVID on campus permeating students and faculty’s vaccine barriers. The decline in statewide cases offers a false sense of security for Denison students and faculty. Positive COVID cases are on the rise in Licking County where Denison University resides. According to the New York Times, there is a seven day average of 126 positive cases a day in Licking County, which is a 46% increase from two weeks ago’s average. October has been filled with the highest average COVID cases in Licking County since the beginning of the pandemic in March of 2020. Denison has created a series of public web pages on their website under the title “COVID-19 Coronavirus” where the university outlines its approach, cases on campus, contact information, information for students, for faculty, for visitors, and more. This page offers real-time data about the situation of COVID at Denison. There were 12 positive COVID cases within the Denison community (students, faculty, and staff) during week one, eight during week two, four during week three, 11 during week four, and three during week five.

As cases remain low, both students and the administration are enjoying a more normal year back on the Hill. “I’m super proud of us. I’m super proud of the way this community has come together to handle COVID,” says Weinberg. “It hasn’t been easy for any of us and I think as a community people have been willing to sacrifice, are sensitive to each other’s needs, all of that has been amazing. I do feel confident that whatever comes our way, we are prepared as a community to deal with it.”