Lula Burke, Editor-in-Chief—

What do an Adam Weinberg email, a 1970’s poster of The Who, and a first edition of the King James Bible have in common?

They’re all archived in Denison’s Special Collections department located in the basement of the Doane Library. The room is seemingly small–a few tables, some vintage class photos hanging on the wall, an out-of-place Herman Miller Eames chair. But behind a locked door is hundreds of years of old photos, Denison memorabilia, signed copies of famous books, and much more.

Though the department is still receiving regular donations of vintage items, they’re also getting additions nearly every day of current items that will define how future generations think of Denison in 2023.

Sasha Kim, 38, is the University Archivist/Special Collections Librarian. She has her Masters in Library Science from Capital University, and explained that items in the collection span from before the college’s formation in 1831 to just a few days ago in 2023. Kim’s main job is to determine what is added to the collection.

“When we get things in, I make the choice about [whether] we keep it, how we organize it in the back to have the right arrangement…if there are conditional problems with something, like if it has mold or mildew on it, how do we preserve it? Do we send something out [to be preserved]?” she said. “I do a lot of the administrative things on that end, and then I also do all of the classes and instruction sessions that come in.”

She works alongside Reference Archivist Colleen Goodhart and several student interns. Kim and Goodhart deal with all of the incoming vintage items in addition to incoming current items.

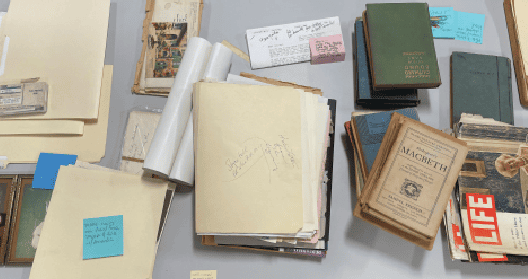

Surprisingly, dealing with the older items has been the easier part of Kim’s job. One of the most recent additions to the collection is an assortment of letters and personal items written by Hal Holbrook ‘48. The letters, on various papers and postcards, sit on the main desk in the archives room waiting to be digitized, labeled, organized, and filed away into the back room.

“We got them after he passed. He had given some of these letters to other people from his estate, and they didn’t know what to do with them. But they were like, we heard that Denison got his original suit from when he did Mark Twain, and they said, would you like this,” she said. “So, we got all of these handwritten letters–copies of them, but also their originals as well–that just tell a story about the different people he interacted with. Many of them are between him and his former Denison professor, who he stayed very close with, almost like a father-son relationship until his passing in his 90s. That was a really big deal.”

Every day, Kim and Goodhart spend time with these items. Kim emphasized the “intrinsic value” of having physical contact with 1920’s fax paper and viewing historical artifacts in person. One of her favorite pieces in the collection is from the Civil War era.

“I found a Civil War deserter’s poster from this area. It says, like, 30 dollar reward if you find these deserted soldiers from Licking County, and it has their names,” she said.

Some things, like the first-edition King James Bible and the many 13th-century Latin manuscripts, were treated with care when they were made and kept safe until they ended up in the temperature and moisture-controlled archives–but others, like posters from Big Red Weekend in the 1970’s, were gems that had to be repaired.

“We also have a poster from when The Who performed here. We had to do a lot of preservation on it because it was crumbling,” she said. “One of our student workers and I worked together and used special repair tape on the back and then we encapsulated it in archival plastic so that it stays safe. It had been rolled up and kept in somebody’s attic.”

This is Eric Wharton’s favorite piece–he is a senior at Denison and a student worker in the archives.

“I really want to make a copy of that but it’s too big to fit in the scanner,” Wharton said, laughing. “You would never think to keep something like that, but to me it’s so sick.”

Other pieces, like Goodhart’s favorite, are so old and rare that they are one-of-a-kind.

“One of my favorite things is this daguerreotype we have of the early women. It’s really cute. It is the class of 1861 from the Young Ladies’ Institute. It’s their class picture,” Goodhart said. “[Imagine] the amount of care that they put into it. Now, we have the digital composite of [students’] heads all put together. But here is this lovely thing that you gave as a gift.”

This idea of “intrinsic value” has been put on display as important Denison artifacts–annual reports, messages from the president, yearly calendars–are solely communicated online. Kim explained that though the department once relied solely on physical copies of items, the archivists have had to shift to digital in recent years.

“Our physical archives go up until about the 2000s-2010s. Everything since then has been digital, and a lot of it hasn’t been saved,” she said. “Around the early 2000s, people wouldn’t write memos, they would send an email. People were not taking film photographs, they were taking digital photographs. And where do those originals go?”

In fact, author and scientist Kathleen Hansen wrote in a 2015 piece that as more and more items are “born-digital” and less likely to be reliably saved, “there is a real possibility that historical research using news archives will become impossible.” Kim explained that finding these digital copies is especially important looking forward, when future generations may want to look at the day-to-day life of a Denison student in 2023, a time when we are posting to social media rather than shooting film.

“One of the big challenges we’ve had is we have the 200th anniversary of the college coming up in 2031, and we’re realizing that ever since the early 2000s, there are some big chunks that are missing,” she said.

Kim cited that much of this is due not only to the increase in digital format, but the assumption that certain things aren’t important enough to be saved. For example, during the beginning of the COVID pandemic, worried students and faculty came to the archives to see what content had been saved from the 1918 Spanish Influenza epidemic. But who would think to archive a 2020 newspaper clipping during a collectively terrifying time?

“So many people were like, can you tell us what we did on campus in 1918. We could see the newspaper articles being written about how everyone should wash their hands. So much of it was similar,” she said. People really liked going back and seeing 100 years earlier how we were going through the same thing. It’s a good example of how people never would think that washing their hands or talking about how many people were sent home with the flu was important. It ended up being very relevant and a very great source for when everybody was feeling very unsure about [COVID],” Kim said.

Today, as student researchers, classes and alumni come into the archives to conduct personal research and “just look around,” Goodhard emphasized the need to keep the archives up to date with things that we might not view as important–such as digital photos from 2014 or emails describing COVID protocol.

“We are a community effort,” she said. “It’s about self-identifying that your things are important enough to put into our shared memory bank. The archives and the things that we hold are very sentimental and emotional because it’s what ties you as a Denisonian today to the Denisonians that were here 50, 60, 70 years ago. The experiences that you have today are different than they had then, but also the human nature of being a college student is very similar.”

Kim asked students to think of the items that are intrinsic to them and of the possible gaps in the archives that need to be filled. She said that her work now is to ensure that everyone’s “voice” is included in the collective history of Denison.

“So, how are you taking pictures? How are you holding onto memories? You might put it on to Instagram, but back then they put it in a scrapbook. It’s the same idea. Being able to see some of these old pictures of somebody who is your age, what they looked like, what dorms they were in, how they decorated them…” she said, “That’s one of the biggest messages–this isn’t just a resource for people to come look at and research in, it’s also a living, breathing being. The shared history of Denison.”